This is my 250th post, and, rather than patting myself on the back about it, I thought I’d put myself in the shoes (pumps?) of a musical theatre writer starting out today. You’ve arrived in New York, where there’s a musical theatre writer for every light on Broadway. Why New York? Well, I’m happy to acknowledge that new musicals do get created elsewhere, but not with the frequency, talent pool to draw on, or stakes.

Which reminds me of the time I traveled to Chicago, with my improv troupe, and observed half a class with the legendary improv guru Del Close. He pooh-poohed the notion that improv could be done in New York or Los Angeles. “You’re going to need the freedom to fail, in order to experiment as you’ll need to. You can do that on stage here in Chicago, but in New York, it’s bound to be in the back of your mind that, on any night, there might be someone in the audience who could make your career. So you’re less likely to take risks.”

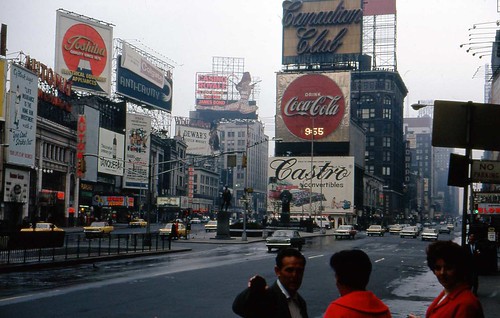

On any given night in New York, you can see a plethora of new musicals, and, I guess, that potential agent, artistic director or producer in the house raises the stakes (better be good!), while, we all know, Nothing Ever Happens In Blaine.

But now I’ve really gotten sidetracked, because I really wanted to talk about Stephen Schwartz, as a young man.

Like you, he arrived in New York after college, and, not like you, he was rather suddenly working with Bob Fosse. It bothers me a bit that Schwartz is sometimes introduced as “Composer of the phenomenally successful Wicked.” when, back in his twenties, he scored the hat trick: three of the longest-running musicals of the 1970s. Now, he did that through a combination of talent and luck, but hey, just-starting-out person, I assume you’ve a great deal of talent, too.

But let’s put talent aside for a moment, and think about the conditions that created a Stephen Schwartz so many years ago. The World of Musical Comedy (as it was then called) that launched Schwartz to stratospheric heights was markedly different from the world we live in today.

For one thing, back then there were creative producers, guys who always had an eye out for new talent. And these were individuals, not corporate entities with board rooms and shareholders to answer to. One of my heroes is Stuart Ostrow: not only did he produce Schwartz’ first Broadway show, he dedicated himself to getting new and innovative musicals on the boards. He didn’t seem to care about the track record of the creators he worked with. Another of his hits, 1776, had a score by a songwriter who had never had a musical produced, and never did again. And he also produced a Bock & Harnick show – after they’d done Fiddler on the Roof.

Another point that nobody seems to agree with: Broadway wasn’t jam-packed with revivals. It was exceedingly rare, in the early 70s, that producers put investors’ money into something audiences had seen before. They understood that this is a creative industry, at its best when it does something new. And I mean truly new: nothing like a faithful adaptation of a well-known film. “Let’s give ‘em something they’re familiar with already” wasn’t the business plan of the earlier era.

And think of Schwartz’s competition on The Street. There was a Sondheim show, a Coleman & Fields, two bombs by Galt MacDermot, a Cryer & Ford, and I’m not knocking those fine writers when I say that, as rival writers go, they’re beatable. Like how other teams look forward to playing the Mets.

Debuting in the Twenty-First Century means going up against, Sting, ABBA, Green Day, Bono and Tupac Shakur. These chart-toppers may know absolutely nothing about writing for character and propelling a story, but hell, the huge conglomerate of corporate producers that runs Broadway now is far more likely to take a chance on rockers who’ve had a huge amount of radio air-play than they are you, who might know something about the making of musicals. And let’s break this down a little. Sometimes, as with Sting, Bono and Sheryl Crow, it may be a getting-on-in-years pop superstar who’s actually sitting down and writing for the stage. Sometimes, as with Green Day, ABBA and The Who, it’s just the rock star deigning to allow their previously-written work to be presented on stage. Tupac Shakur, of course, is dead, so don’t blame him for this state of affairs.

Am I Rewriting History? …is a song that just popped into my head. It’s a collaboration between Stephen Schwartz and Steven Lutvak. And maybe I can lift this depressing post a little by mentioning Lutvak’s triumph. Amidst all the jukebox shows… Amidst the myriad ill-advised film adaptations that cynically hoped to rope in ticket-buyers who had fond memories of the movie being musicalized… Amidst all the oeuvres by past-their-prime rockers trying their hand at musical theatre for the novelty of climbing a mountain they’ve never climbed… Lutvak’s first Broadway musical A Gentleman’s Guide To Love and Murder, opened last fall and blew away the competition, artistically, getting the best reviews of the season and, to no one’s surprise, the Tony Award for Best Musical. It can be done, folks. Even today where, instead of the fertile ground that produced a Schwartz, we’ve an asphalt expanse, asphyxiating new growth – lo and behold, a sprig breaks through.

Posted by Noel Katz

Posted by Noel Katz