Here’s one of musical theatre’s most groan-producing forced rhymes:

You are the light of the world

But if that light’s under a bushel

It’s lost something kind of crucial

(Some people quote the Bible; I quote musicals. Even when they’re purporting to be quoting the Bible.)

So, I’m about to give my internationally famous subjective musical theatre history in Los Angeles. (August 1-4, 2018) It’s the first time, in the eighteen-year-history of the History, that it’s been offered to the general public. (Register now at http://nmi.org/events/a-subjective-history-of-musical-theatre/ ) So, I really ought to say a few words about it but there’s a problem.

If I tell you, with proper honesty, about the reactions of those who’ve previously attended, it’s going to sound like bragging. And I don’t like to brag. But I really shouldn’t keep my light under a bushel. I see the rapt attention in everyone’s eyes. I engage the learners in a conversation about musicals and how they came to be – it’s imprecise to call them an audience. But, when it’s done, inevitably, every time I do it, a group will come up to me and say “Wow, that was amazingly entertaining. I learned so much.”

These were theatre students, accustomed to receiving a fabulous education – some had BFAs, MFAs, there may have been a PhD. Others made a choice to avoid college because they couldn’t picture themselves listening to lectures in a hall. Is what I do a lecture? I don’t think that’s a good word for it. I fill our time with jokes, with much back-and-forth; I run to the piano to sing illustrative songs. I even execute a move I saw in a Fosse show. And, at certain points, I make people cry. I tell the life story of a musical-writing hero of mine in such dramatic fashion, well, the last time I did this there was an audible gasp.

The talk sprung into being when I was given the floor at an acting school with a curriculum so packed, nobody had time for history. Some students knew the classics, but not the new. Others, the reverse. And then there were people who exclusively were into Sondheim shows. There were no grades, no tests, no consequence, really, for not apprehending what I put out there. Teachers, in traditional classrooms, have implicit sway: “Learn this, or get a bad grade <maniacal laugh>.” Take that away, you’ve got my kind of challenge! If I talked fast enough, if I suddenly broke out into song when nobody expected it, if good jokes came frequently enough, folks would eat it up. Learn. Understand.

And, thank God, it’s safely removed from traditional academia. The stories I tell needn’t be the gospel truth (or the Godspell truth, for that matter). No one was going to stop me if I injected my opinion. If I think a particular show is awful, I say so, and get to explain why. And make fun of it in such a way, you’ll laugh your head off.

Since it’s a dialogue, I suspect I’ll field some questions. What’s on many minds these days is the skittishness involved in the current revivals of a couple of Golden Era classics on Broadway. It would seem that producers are uncomfortable with presenting pre-feminism musicals to a post-feminist audience. Broadway, of course, is a business, and the supposition is they’ll sell more tickets to bowdlerized Rodgers & Hammerstein or a Lerner & Loewe with a reinterpreted ending than they would the pure unadulterated hits the world has loved for decades.

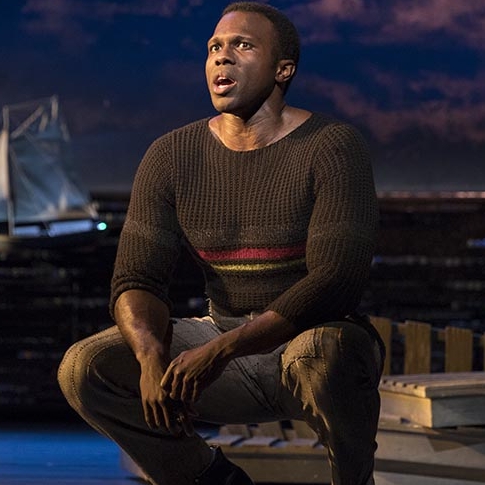

I’ve written before about the particularly ludicrous charge that Carousel somehow condones or romanticizes wife-beating. It rather explicitly does not. And since I once played the character uttering the line, I can quote you exactly what the Heavenly Friend says the moment long-dead Billy slaps the hand of his daughter:

Failure! You struck out blindly again. Is that the only way you know how to treat those you love? Failure!

This messenger from God is saying what Hammerstein wants us all to hear, that wife-beating or even daughter-slapping is never acceptable. And yet the text is radically altered to make it even more acceptable to today’s audience.

One property that Rodgers and Hammerstein felt couldn’t work as a musical was George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. In that fine play, a lower class woman stands up for herself, getting the best, in argument, of a tony Mayfair scholar. Lerner and Loewe created the longest-running musical, ever (beating Rodgers and Hammerstein’s record), My Fair Lady, by leaving Shaw’s arguments in, virtually intact. I think the best word for it is proto-feminist, since it pre-dates what we call the feminist movement by a few years. 62 years later, though, powers-that-be saw the need to tip the scales a little further in favor of the reconstituted flower peddler, who now marches out of the theatre in response to the final power play.

I’ve admired the work of the directors, Jack O’Brien (Carousel) and Bartlett Sher (My Fair Lady) in the past, but this seems a good definition of hubris. Rodgers and Hammerstein crafted what was named the twentieth century’s greatest musical. Lerner and Loewe crafted the longest-running show to open during the 1950s. Those writers are geniuses – you think you can do better?

Now, I’m not saying you have to love those shows. A Sondheim character sees My Fair Lady and says “I sort of enjoyed it.” But, please, have some sense of historical context. Carousel was written for a war-time audience, one that surely contained war brides and war widows. Rodgers and Hammerstein reassured wives of soldiers that they’d made the right choice, marrying those who served. Imagine if your husband died in World War Two and you get to watch a widow hearing her long-dead husband utter, “Know that I loved you.”

To appreciate this, though, you might have to have a sense of history. And those current producers don’t trust that ticket-buyers today have that. But one can always learn history. Which is why you’re going to attend my Subjective History of Musicals. You’ll learn; you’ll laugh; you’ll love musicals more.

Posted by Noel Katz

Posted by Noel Katz