Now that Stephen Sondheim’s entered his 90th year (I’m writing this a day after his 89th birthday), a few thoughts on what he learned from Oscar Hammerstein during his second sixth of life. They met when he was roughly 15. Before meeting the old master, Sondheim hadn’t even considered writing musicals. The year the protégé turned 30, and had two wonderful musicals running (lyrics only), Hammerstein died at the age of 65. Also that year, there were two Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals on Broadway.

And I might as well name them: Gypsy was playing, and West Side Story had returned from the road; Flower Drum Song, a funnier-than-most R&H piece, ended its run, and The Sound of Music opened and was a hot ticket. Of this quartet, I far prefer the innovative shows with Sondheim lyrics; both have scripts by Arthur Laurents and direction by the estimable Jerome Robbins.

It is, of course, tragic that Hammerstein died so young: think of what more he might have given us! On the flip side, it’s wonderful that Sondheim has lived so long. So, there’s no what-might-have-he-given-us if he lived past 65. He did, and gave us exactly two off-Broadway musicals, Assassins and Road Show. No debilitating diseases slowed him; it’s just been a rather fallow quarter century. The shows he created from age 40-65 were so excellent – Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd and Sunday in the Park With George among them – I, for one, can’t help feeling disappointment that his productivity knob has turned down so drastically.

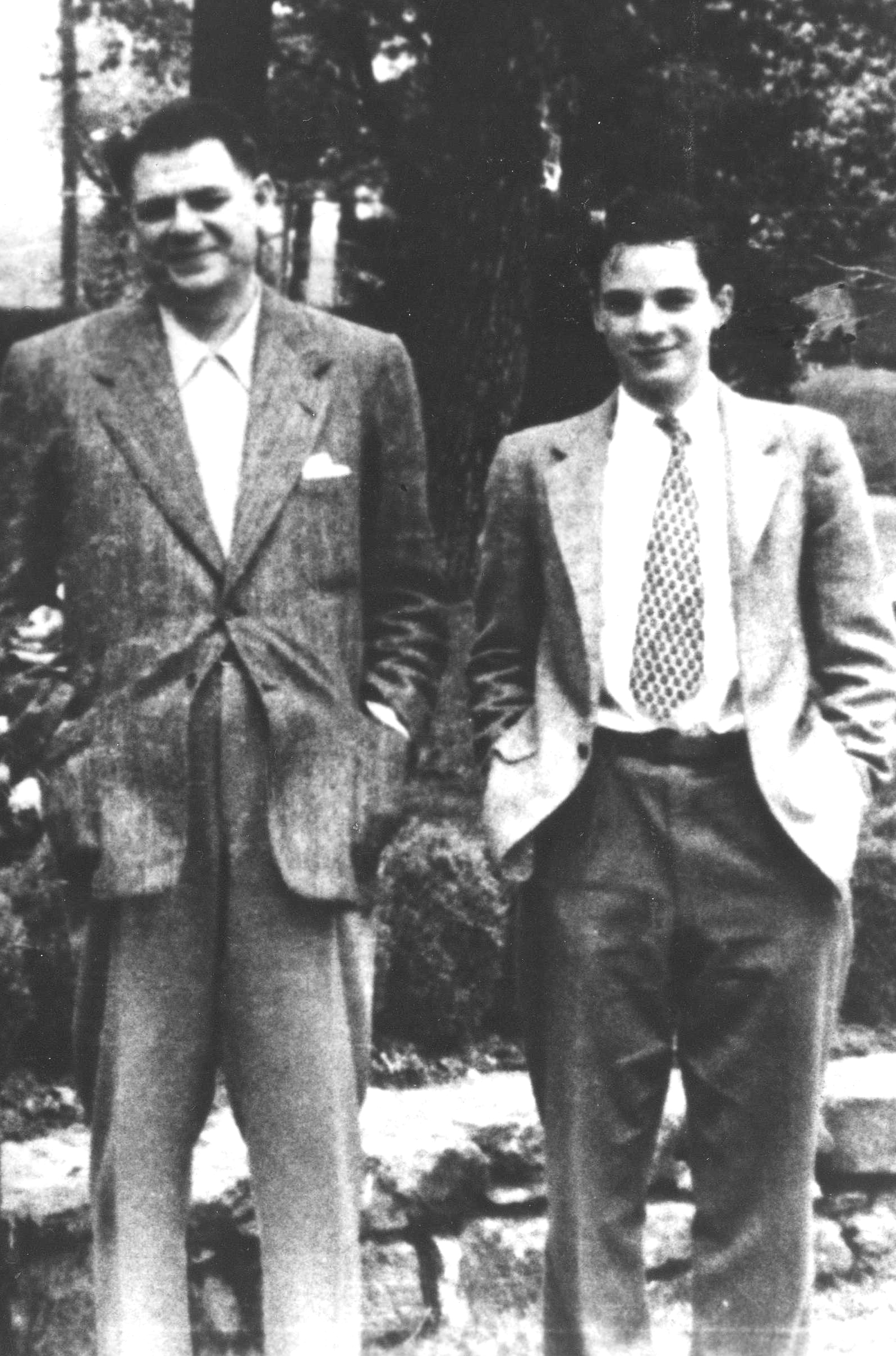

Better to picture him as a teenager soaking up wisdom from his Bucks County neighbor. It’s always fascinated me that little Steve presented a script for his friend’s dad to comment on and boy, did he comment! This was the greatest single lesson in musical theatre writing ever given, and what I’d give to have been a fly on that wall. We have information about Hammerstein’s understanding of theatre from his essential forward to his book of lyrics; of course, the shows themselves exemplify his aesthetic, although there were usually collaborators (besides Richard Rodgers) adding their own great thoughts.

Hammerstein cared about structure, and you may have noticed there’s usually a main couple (such as the Bigelows) and a contrasting pair (like the Snows). If one is serious, the other is likely to be comic. His lyrics abound in well-chosen nature imagery. (Busy as a spider spinning daydreams.) And the aspect most on my mind these days is concision, the notion that when you tell your story through song, things move faster than they would in unsung dialogue.

Sondheim has also peppered his published volumes of lyrics with fascinating commentary. And he mentions an “oedipal thrill” of criticizing his mentor’s lyrics when he was a successful adult. One can only imagine his reaction to “like a lark who is learning to pray” although I’ve always felt it plausible that Hammerstein meant “prey” – on little worms, or whatever larks eat.

And when the cat’s away, the mice are at play. Once the mentor’s watchful eyes were shut for good, the mentee wrote substantively different musicals, as if he at last felt free to rebel.

Short & Sweet/Long & Sour

The first of the Sondheim shows to open in the sixties was A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and that long title lived up to its one adjective. The book, by Larry Gelbart and Burt Shevelove, speeds along splaying jokes across the footlights. You never stop laughing until…the songs. They attempt to be funny, but manage to slow things down, evoking smiles (sometimes pained: “irascible!”) rather that guffaws. Had Oscar lived to comment, he might have restated the lesson about concision. Just when the second act is hurtling forward like a dislodged Ferris wheel, a battleaxe takes stage and diverts us from all that’s good with an ungainly and mirthless scena. I wanted this show to be over without the fat lady singing, thank you very much. To his credit, Sondheim’s repeated his teacher’s point about concision many times since, rather concisely.

Whither structure?

The era when all shows needed to resemble the Rodgers and Hammerstein classics couldn’t last forever. The many Broadway flops of the late sixties made many feel it was time for something new and Sondheim’s 1970 hit, Company, shattered perceptions of what a musical should and could be. It’s refreshingly different, the first of many innovative entertainments fashioned with director Hal Prince. And we can celebrate this busting of the mold but must acknowledge that what’s being undone was the template Oscar created.

Company doesn’t have much of a plot. It’s a set of scenes about marriages, bemusedly witnessed by a swinging bachelor named Bobby. What happens to Bobby is not something we ever care much about, and his decision to connect seems a tacked-on ending. We don’t really track his feelings; his actions are few. Later, two works in collaboration with librettist John Weidman similarly present scenes that don’t tell the story of characters: Pacific Overtures and Assassins. It might be fair to call these “revuesicals.”

“A musical play” was under the title of the Rodgers and Hammerstein genre-busters. For them it was of primary importance to tell a moving story about realistic people, presented as seriously and cogently as any play.

An un-love story

But the most obvious hallmark of the Golden Era was that, without exception, musicals concerned love. One went with the expectation that love songs would be sung, and, it was to be hoped, you’d be moved by the ups and downs of romances.

It’s here where I believe ol’ Oscar would have been most surprised and dismayed by what his pupil hath wrought. Bobby doesn’t love anyone, and Follies and A Little Night Music center on unhappy marriages. Into the Woods has the temerity to show fairy tale characters commit adultery. The Sondheim musicals, so rarely showing love, contain very few love songs. He denies audiences one of the main things they used to come to musicals for – an odd omission, probably willful.

Hammerstein & Sondheim shared a collaborator: Richard Rodgers, desperate to replace his late partner, glommed on the supposed protégé for Do I Hear a Waltz? It was an unhappy experience for them both, probably owing to Sondheim’s discomfort or distaste for writing lyrics about love.

Posted by Noel Katz

Posted by Noel Katz