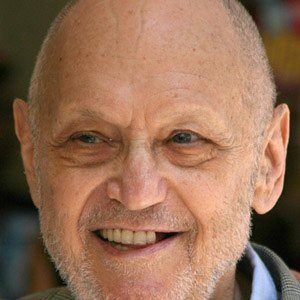

This June has been so busy, I’m late in acknowledging Charles Strouse’s 90th birthday, which was June 7. And I’m going to cut myself a break by reprinting, here, something I wrote for a Big Time Professional Blog. I have it on good authority that Martin Charnin finds my premise ludicrous. So… enjoy!

People usually credit Hair with bringing the sound of rock & roll to the Broadway stage, but one composer effectively inserted rock into his scores years earlier: Charles Strouse. At a time when pop culture and Broadway were parting ways, Strouse bridged the gap, incorporating contemporary sounds into his scores for Bye Bye Birdie, All American, Golden Boy, It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman, Applause, and even Annie. Songs from his shows were some of the only Broadway tunes to get significant radio play in the 1960’s.

And it started as a joke. In 1960, four funnymen who’d never written a musical professionally before, got together to make fun of a cultural phenomenon. Elvis Presley had cast a spell on young America. He sang a new kind of music and had a different kind of personality than previous stars. He wasn’t particularly articulate in interviews, pictures showed him with a sullen sneer, and his hip-swinging while singing struck a lot of people as obscene. Of course, those words could describe a lot of subsequent rock stars, but Elvis-the-Pelvis was the first. Gower Champion (director), Lee Adams (lyricist), Michael Stewart (librettist) and Charles Strouse (composer) thought this was so amusing, they wrote a show about it: Bye Bye Birdie.

Gower Champion had a choreographic vision involving women swooning and losing control of their muscles as their dreamboat gyrates. Lee Adams noted how rock & roll lyrics often seem to have a thinly veiled sexual content. (“When I sing about a girl, I really feel that girl.”) Michael Stewart had written for Sid Caesar’s television show and would have known Caesar’s musical sketch, You Are So Rare To Me, in which one syllable gets broken into unconnected pulses, just like the endless “baby” in the bridge of One Last Kiss – lampooning rockers’ vocal style.

But Strouse goes beyond mere Presley parody. He sets up different musical landscapes for the two warring generations. The adults sing in styles other than rock – Kids and Rosie are, in effect, old people’s music. Meanwhile, the teen ballad, One Boy, uses a shuffle rhythm and back-up singers in the manner of 50s pop, and when Birdie and the teens sing together (Got a Lot Of Living To Do) Strouse marshals the power of a rhythmically pulsed major seventh, a chord not often heard in musicals of the time, but emerging in rock (e.g., This Boy).

After the breakthrough success of Bye Bye Birdie, Strouse and Adams teamed up with another of Sid Caesar’s gagmen, Mel Brooks, to pen All American. The show also depicted a generational divide, this time between college students and their professors. While the show’s one hit, Once Upon a Time, was a duet for the oldsters, the ingénue has a naughty number called Night Life. Its jazzy vamp keeps accenting the seventh of the scale on an off-beat, where one doesn’t expect it. She’s rebellious and sexy in the way the teenage girl of Bye Bye Birdie is not allowed to be. (You wouldn’t know this from watching the Birdie movie featuring the too-erotic-to-be-believed Ann-Margaret.)

When Strouse and Adams teamed with Clifford Odets to musicalize his play, Golden Boy, the challenge was to represent contemporary urban African-Americans with some level of authenticity. Broadway hadn’t heard anything quite like it. Strouse produced a score that sometimes rocks, sometimes swings and culminates in an energetic gospel funeral. Is Golden Boy a rock musical? It’s certainly soulful, and the definition of what constitutes “rock” gets revised over time. Many of the songs – even a traditional show tune like Don’t Forget 127th Street – end with repetition and quasi-improvisational jazzy playoffs more common in rock records than theatre.

Writing It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman, Strouse & Adams faced a familiar scenario: a happy chorus giddy with admiration for an unusual superstar. Whether he was conscious of the connection with Bye Bye Birdie or not, Strouse rocks We Need Him, It’s Super Nice and Lois Lane’s It’s Superman. She references a “schoolgirl fantasy” and so seems, in a way, Birdie‘s Kim McAfee all grown up. The hit that emerged from the score, You’ve Got Possibilities, was once sung by Lady Gaga. (I should know: I was at the piano.)

Applause was another hit set in present-day New York. In a production number called But Alive, the leading lady visits a gay bar and dances with adoring fans. They’re accompanied, naturally, by the groovy strains of 1970. This was after Hair, and Broadway audiences, by that point, had become more acclimated to rock music in the theatre.

In fact, the culture, at large, had a new attitude about rock songwriting by the 1970s. What had seemed like inarticulate utterances of hormone-crazed teens grew, in seriousness, as adult performers sang out protests against the war in Vietnam, racial prejudice and other weighty issues. Making fun of young people’s music eventually seemed a tired joke, which may account for the box office failure of Strouse & Adams’ sequel, Bring Back Birdie.

Last night I saw Annie and was puzzled by the use of a rock beat in a show set during the 1930s. What’s up with that? I can vividly remember hearing the original cast album for the first time: it began with a small brass choir, like you might hear on a street corner at Christmas. Just as I was thinking how much I love brass choirs, the music abruptly shifted to a staccato repeated chord on electric instruments. This struck me as an odd choice at the time – an inappropriately contemporary way of coloring the rebelliousness of besieged orphans – but many years later Jay-Z’s version of It’s a Hard Knock Life went platinum. So why question it? Charles Strouse invented the rock musical, and keeps finding opportunities to rock out whenever he can. The guy can’t help it.

Posted by Noel Katz

Posted by Noel Katz