When I was in college, the theatrical attorney who’d introduced my mother to my father introduced me to a client of his, producer Ted Mann. It was explained to me, in no uncertain terms, that this was a Great Man of the Theatre. At the time, I accepted this designation without questioning it. But a few years later, I looked up his credits. In the 1950’s, Ted co-founded The Circle in the Square theatre. Through his association with legendary director Jose Quintero, he produced three great plays by America’s two greatest playwrights: Summer and Smoke, by Tennessee Williams; and Long Day’s Journey Into Night and The Iceman Cometh, by Eugene O’Neill. Pretty impressive, those. Credits that validate the sobriquet, Great Man of the Theatre.

Years later, around the turn of the century, I started working for him. He looked to be older than God. It never left my mind that Ted was a Great Man of the Theatre, and that he was unlikely to be around much longer. A dozen years went by, and Ted was still there; death finally came in February, 2012.

Now, the trouble with my reminiscing about my times with Ted is that every anecdote inevitably makes Ted seem like a doddering old fool. You have to keep in mind that six decades ago, he was an enterprising young lawyer with a love for the theatre. And he started something pretty special off-Broadway and even Important. We worked together on many musicals, including some new ones: he the credited director; I, the credited musical director. And yes, I’m implying that in some cases, we didn’t really deserve the credit.

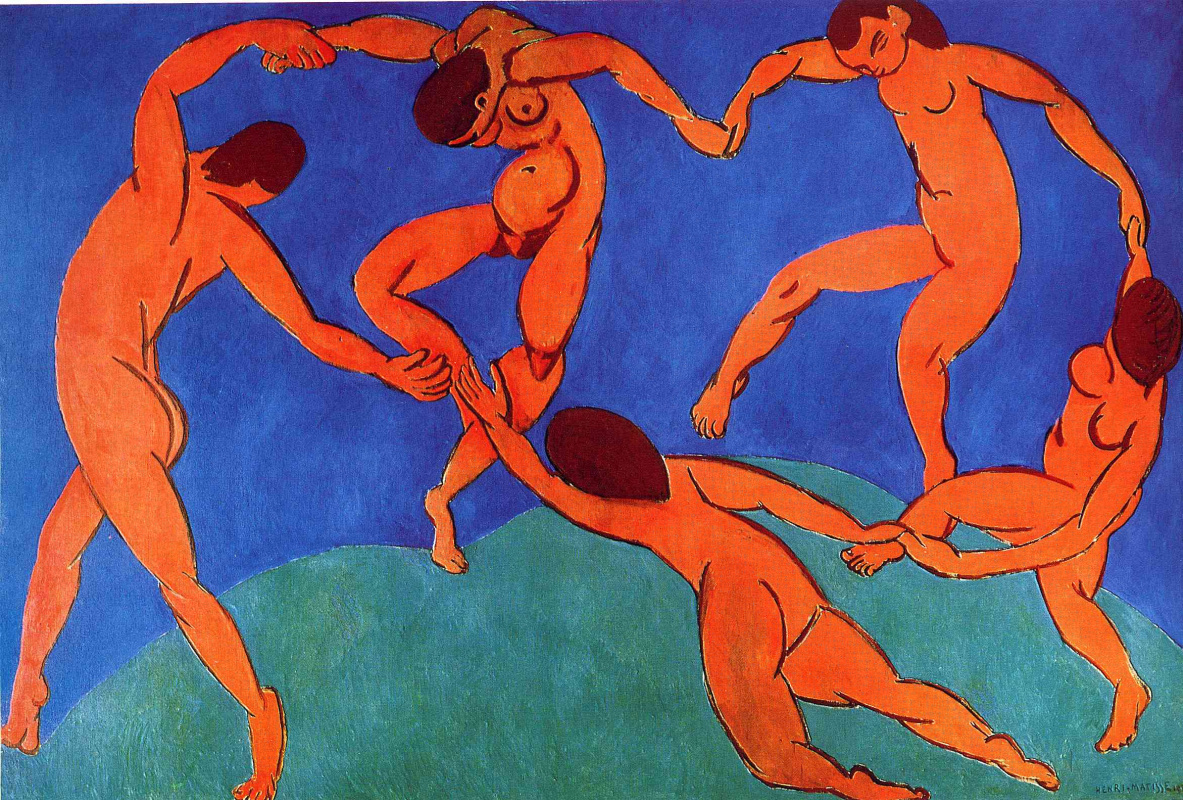

On one original musical, for instance, I did precious little other than teach the performers their parts. I attended one creative meeting in his office – it contained a Tony Award along with some tasteful photographs of a nude woman – but my job there was just to assure everybody we’d be able to find a competent cast. The composer, a rock musician with a unique look – a carefully coifed long-hair and long-beard combo, would provide backing tracks for performers to sing to. So, no live musician, and very little for me to do (I attended no rehearsals).

But there were other projects on which Ted did very little. With careful deference to the Great Man of the Theatre, the choreographer would often take over the de facto staging job, for the simple and sad reason that Ted was not competent, mentally, to stage the show. Or understand that he was director in name only. Eight years ago, in our second or third week of rehearsal of Godspell, he asked whether we couldn’t possibly depict the crucifixion in a non-traditional way. Of course, we weren’t planning to depict the crucifixion in a traditional way. No Godspell production does that. Which Ted would have known if he’d ever seen Godspell. Or bothered to read the script.

Yes, folks: In the overwhelming majority of shows I worked with him on, he didn’t read the script prior to the first rehearsal. Often, we’d start with the cast doing a read-through, and he’d be genuinely surprised by jokes, plot twists and other surprises. The notes he gave as director, nine times out of ten, had to do with loudness and diction. He was hard of hearing, and the actor who didn’t project at the top of their lungs would earn his scorn.

He liked me, though. He’d stop me in the hall so we could swap opinions about Broadway shows we’d seen. And, on one extraordinary occasion, he was particularly complementary. A scheduling conflict had kept the actor playing the minor role of a cop named Murphy away from our rehearsal of a non-musical scene. So, I thought I’d help out by standing in his spot, holding his script, bellowing out his lines. Afterwards, Ted gave notes on the scene, including “Murphy: Very good. Keep it up.” It seems he honestly didn’t know I wasn’t the actor, a hirsute ex-marine twenty years my junior.

Less happily, he could throw his authoritative weight around, arbitrarily, trouncing on emotional toes. I can recall a strong actress, with a good sense of herself, reduced to tears; she was coming from a rehearsal with him to a rehearsal with me and much of our time got used up comforting her. Once, we’d been denied access to the Circle-in-the-Square Theatre by the Broadway show Ted had rented the space to. Ted was sure we could work out some deal, but the rest of us on the production team, as well as the cast, knew that we’d already rented a different space, and not one in the round. Ted was too blind to read the handwriting on the wall and insisted on staging the entire show with the actors playing the 360-degree sweep. As we all knew in advance, the show then had to be restaged for a proscenium set-up.

When Ted spoke, I’d listen, eager to soak up some of the knowledge that made him legendary. Poignantly, none ever came. Perhaps Ted’s greatness was only as a producer. The first Mann-directed musical I attended, a Pal Joey revival in which the two stars jumped ship during rehearsals, had the theatre set up like a cabaret, with short tables in front of front-row audience. Naturally, people put Playbills and reading glasses on these. Midway through the first act, dancing waiters came by, and, on a particular beat, whipped away the tablecloths. Just like the standard magicians’ trick but here was no magic: debris went flying everywhere.

I’m saving one Ted tale, the longest, for last, but first must remind you that just because a person does some frustrating things in his dotage, that doesn’t undo the stuff that makes one a Great Man of the Theatre in the first place. And if I’ve anything of a cautionary nature to say here, it is: don’t be enraptured by a résumé. Make sure the Greatness still persists.

Around fifty years ago, Ted started the Circle-in-the-Square Theatre School and this gave him the right to drop in, unannounced, on any class within its walls. Would his visit be disruptive? It was a concern. Last year, a teacher of a certain age, Sara, received such a visitation. She cautiously but cordially explained to Ted that we were in the process of suggesting songs that individual students should look at. Every title mentioned by Sara, me, or a student, made Ted go “What?”

If it was the student who’d spoken, Ted made the point, a bit meanly, that students should learn to speak up. Meanwhile, Sara had to repeat each title to him, and he’d either nod with recognition, or tell us he didn’t know the particular song.

This went on for some time, until Ted changed the subject: “Sara, you were never a performer.”

This was quite an odd thing for him to say. And false. Showing the deference due to a Great Man of the Theatre, she could only answer honestly. “Actually, Ted, I started my career as an actress in musicals.”

To which Ted said “And then you got pregnant.”

Sara was a little taken aback, and said “Noooo…”

Ted: “But you weren’t on Broadway.”

Sara: “Actually, Ted, I was.”

Ted wanted to know what show, and Sara described it. She’d taken over a role from an actress whose name Ted recognized.

Then, Ted said “And then you got pregnant.”

At this point, everybody in the room realized they were listening to an insane person. Sara politely said that parenthood was decades after her debut on The Street.

She continued to give details of her career. How friends in casts began to ask her to coach their auditions, and soon she was teaching her own class.

It was clear to me Sara was about to describe how she became a director. “My classes were filling up, so many people wanted me to coach them, that soon I wasn’t going out on auditions any more. And as this was going on, I felt something in the pit of my stomach.”

To which Ted said “You were pregnant?”

No, the desire to direct.

Now, somewhere around this point, Ted realized his repetition of the line was making people laugh, so, at last, he appeared to be in on the joke, and continued saying this to be funny.

Sara, assuming Ted must have noticed her age and could do the math, said that her son is twelve years old.

Ted didn’t do the math, and asked when Sara had come to Circle. “Eleven years ago” she said. And Ted said “So you weren’t pregnant when you got here.”

To which Sara said, “Actually, Ted. I wasn’t pregnant at any point. My son is adopted.”

“Well!” said Ted, “Adoption is a wonderful thing.”

On that we could all agree. Class was over. La commedia è finita.

Posted by Noel Katz

Posted by Noel Katz